Sortuj:

Kolekcja

Data

| Lp | Szczegółowe ID | Pisarze | Kolekcja | Data |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Rota 1, Księga Ziemska 1, Karta 11, Kalisz | PISARZ 1 | Kalisz | 1401 |

| 2 | Rota 2, Księga Ziemska 1, Karta 11, Kalisz | PISARZ 1 | Kalisz | 1401 |

| 3 | Rota 3, Księga Ziemska 1, Karty 12 — 12v, Kalisz | PISARZ 2 | Kalisz | 1401 |

| 4 | Rota 4, Księga Ziemska 1, Karta 12v, Kalisz | PISARZ 2 | Kalisz | 1401 |

| 5 | Rota 5, Księga Ziemska 1, Karta 14v, Kalisz | PISARZ 2 | Kalisz | 1401 |

| 6 | Rota 6, Księga Ziemska 1, Karta 14v, Kalisz | PISARZ 2 | Kalisz | 1401 |

| 7 | Rota 7, Księga Ziemska 1, Karta 15v, Kalisz | PISARZ 2 | Kalisz | 1401 |

| 8 | Rota 8, Księga Ziemska 1, Karta 15v, Kalisz | PISARZ 2 | Kalisz | 1401 |

| 9 | Rota 9, Księga Ziemska 1, Karta 15v, Kalisz | PISARZ 2 | Kalisz | 1401 |

| 10 | Rota 10, Księga Ziemska 1, Karta 16, Kalisz | PISARZ 2 | Kalisz | 1401 |

| 11 | Rota 11, Księga Ziemska 1, Karta 16v, Kalisz | PISARZ 2 | Kalisz | 1401 |

| 12 | Rota 12, Księga Ziemska 1, Karta 19, Kalisz | PISARZ 2 | Kalisz | 1401 |

| 13 | Rota 13, Księga Ziemska 1, Karta 19, Kalisz | PISARZ 2 | Kalisz | 1401 |

| 14 | Rota 14, Księga Ziemska 1, Karta 20v, Kalisz | PISARZ 2 | Kalisz | 1401 |

| 15 | Rota 15, Księga Ziemska 1, Karta 27, Kalisz | PISARZ 2 | Kalisz | 1401 |

| 16 | Rota 16, Księga Ziemska 1, Karta 27v, Kalisz | PISARZ 2 | Kalisz | 1401 |

| 17 | Rota 17, Księga Ziemska 1, Karta 27v, Kalisz | PISARZ 2 | Kalisz | 1401 |

| 18 | Rota 18, Księga Ziemska 1, Karta 28, Kalisz | PISARZ 2 | Kalisz | 1401 |

| 19 | Rota 19, Księga Ziemska 1, Karta 28, Kalisz | PISARZ 2 | Kalisz | 1401 |

| 20 | Rota 20, Księga Ziemska 1, Karta 28v, Kalisz | PISARZ 2 | Kalisz | 1401 |

| 21 | Rota 21, Księga Ziemska 1, Karta 28v, Kalisz | PISARZ 2 | Kalisz | 1401 |

| 22 | Rota 22, Księga Ziemska 1, Karta 29, Kalisz | PISARZ 2 | Kalisz | 1401 |

| 23 | Rota 23, Księga Ziemska 1, Karta 29, Kalisz | PISARZ 2 | Kalisz | 1401 |

| 24 | Rota 24, Księga Ziemska 1, Karta 29, Kalisz | PISARZ 2 | Kalisz | 1401 |

| 25 | Rota 25, Księga Ziemska 1, Karta 29v, Kalisz | PISARZ 2 | Kalisz | 1401 |

Kontynuując przeglądanie e-ROThA zgadzasz się na korzystanie z plików cookies.

Proszę przeczytaj nasz regulamin plików cookie.

eROThA i zespół projektowy

eROThA

eROThA (czyli Elektroniczne Repozytorium Rot Wielkopolskich) to ogólnodostępna elektroniczna baza danych powstała w wyniku realizacji projektu badawczego o nr 2014/13/B/HS2/00644 finansowanego ze środków Narodowego Centrum Nauki. Repozytorium powstało w oparciu o materiały archiwalne zawierające najstarsze (poza nazwami własnymi, glosami i tekstami religijnymi) zapiski staropolskie w łacińskich księgach sądów ziemskich z późnośredniowiecznej Wielkopolski z przełomu 14 i 15 wieku (1386-1446). Polskie fragmenty to zapis przysięgi świadków w procesach ziemskich. Materiały te znane są historykom i językoznawcom nie tylko z archiwów, ale z wielu wydań opublikowanych na przestrzeni późnego wieku dziewiętnastego i w wieku dwudziestym (dokładne odniesienia i bibliografię można znaleźć w Kowalewicz i Kuraszkiewicz 1959: 6-9; Jurek 1991: x-xi; Trawińska 2009: 345-346). eROThA bazuje na najpełniejszym wyborze przysiąg wydanym w monumentalnej pracy edytorskiej Kowalewicza i Kuraszkiewicza (1959-81), która stanowi podstawę prac digitalizacyjnych oraz konstrukcji cyfrowego repozytorium. Jako przedsięwzięcie interdyscyplinarne, platforma wykorzystuje nowoczesne technologie w celu zestawienia zawartości wydania z wysokiej jakości skanami materiału źródłowego (ok. 6000 stron rękopisów) oraz z warstwą specjalistycznej analizy językoznawczej (więcej na ten temat w Wielojęzyczność i zmiana kodów i Od wydania do repozytorium cyfrowego). Podjęta w projekcie digitalizacja nie tylko zabezpiecza bezcenne, często już w bardzo słabym stanie zachowania, archiwalia, ale przede wszystkim umożliwia dostęp do tekstów źródłowych szerokiemu gronu historyków, historyków prawa, językoznawców i wszystkim zainteresowanym odbiorcom. Opublikowanie wysokiej rozdzielczości skanów dokumentów źródłowych, czyli dokumentacyjny aspekt projektu, otwiera je także dla nauk pomocniczych historii, takich jak dyplomatyka, paleografia, kodykologia, czy szeroko pojęte badania nad materialnością średniowiecznych artefaktów.

Podstawą prezentacji na stronie jest oznaczony na faksymiliach czerwoną ramką tekst roty, czyli przysięgi sądowej, wraz kontekstem łacińskim, tj. w większości przypadków z proceduralnym wstępem (więcej na ten temat w Czym jest „rota” oraz problemy selekcji). Zestawione z faksymile wersje tekstowe zawierają w przybliżeniu ten właśnie fragment rękopisu. Niekiedy wersja tekstowa obejmuje także następujący po rocie dodatkowy element, także o charakterze proceduralnym. Nazwa repozytorium eROThA wywodzi się właśnie ze słowa „rota”, zawierając w sobie dwie wersje pisowni: z i bez h. Pisownia „rotha” może zostać uznana za wersję zlatynizowaną etymologicznie słowiańskiego źródłosłowu (Kopaczyk-Włodarczyk-Adamczyk 2016: 20, przypis 6), podkreślając jednocześnie płynność podziałów między leksykonem rodzimym a zapożyczonym w rejestrze prawnym. Skrótowa nazwa wskazuje także na główny nurt zainteresowań projektu: zjawisko wielojęzyczności. W nazwie platformy internetowej zawiera się także anagram angielskiego odpowiednika słowa przysięga (oath ~ eROThA).

Zespół projektowy

- dr hab. Matylda Włodarczyk, UAM

- dr hab. Joanna Kopaczyk, Glasgow

- dr Elżbieta Adamczyk, Wuppertal

- dr Olga Makarova (historyk języka, polonista)

- dr Łukasz Berger, UAM (filolog klasyczny)

Poznańskie Centrum Superkomputerowo-Sieciowe

- dr Michał Kozak

- mgr inż. Marcin Werla

- mgr inż. Arkadiusz Margraf

Archiwum Państwowe w Poznaniu

- kustosz Zofia Wojciechowska

- mgr Tomasz Balcerek

Wielojęzyczność i zmiana kodów

Źródła archiwalne z okresu średniowiecza i wczesnej nowożytności najczęściej nie są świadectwami historii jednego języka, dowodzą za to wszechobecnej wielojęzyczności. Zjawisko to, rozumiane jako posługiwanie się nie jednym, a wieloma kodami (językami, dialektami, żargonami), było i jest normą w komunikacji, jednojęzyczność zaś stanowi raczej konstrukt badawczy zakorzeniony w 19-wiecznej ramie filologii narodowych, niż rzeczywistość interakcyjną. Języki nie wyewoluowały w całkowitej izolacji, we wszystkich znajdujemy ślady kontaktu i mieszania się społeczności porozumiewających się różnymi kodami, wpływy zewnętrzne, zapożyczenia, itd. Jednym z najbardziej złożonych efektów kontaktu między użytkownikami różnych języków, dialektów czy kodów jest zjawisko przechodzenia między nimi, tzw. code-switching.

Zmiana kodów znajduje się w centrum zainteresowania językoznawców co najmniej od 50 lat, a grunt pod to zainteresowanie położył zmierzch nurtu strukturalistycznego i następująca po nim era socjolingwistyki oraz tzw. przełom pragmatyczny. Na przestrzeni ostatnich dekad zmiana kodów stała się także jednym z głównych nurtów badań językoznawstwa historycznego, które obecnie bardzo intensywnie poszukuje ram teoretycznych i metodologii badań wielojęzyczności w tekstach pisanych z mniej czy bardziej odległej przeszłości. Motorem rozwoju tego kierunku badań jest także postępująca rewolucja cyfrowa, która objawia się rozwojem językoznawstwa korpusowego, oraz jego fundamentów, czyli elektronicznych baz danych konstruowanych z myślą o poszerzeniu zaplecza empirycznego badań nad komunikacją, interakcją oraz strukturą języka, także w jego historii. Oczywiście rozpowszechniona codzienna interakcja za pomocą mediów elektronicznych stanowi nową platformę kontaktu multimedialnego użytkowników posługujących się różnymi, często więcej niż dwoma, językami. Zapis takiej interakcji stanowi także naturalne pole badawcze dla teorii i metod badania zmiany kodów w tekstach pisanych.

Pomysł na stworzenie bazy dwujęzycznych ksiąg sądów ziemskich z Wielkopolski wpisuje się w powyższe trendy w badaniach historii języka, dostarczając narzędzie umożliwiające dostęp i zbadanie zmiany kodów w źródłach mało znanych w wersji archiwalnej szerszemu gronu mediewistów czy historyków języka. Jednocześnie baza zawierająca najstarsze zaświadczone wypowiedzi staropolskie jest odpowiedzią na rosnące szczególnie na zachodzie Europy zainteresowanie rozwojem pisma i wczesnych zapisów języków wernakularnych, przede wszystkim słowiańskich, jako technologii i kultury piśmiennej w obszarze Europy Środkowo-Wschodniej (np. badania publikowane w Utrecht Studies in Medieval Literacy wydawnictwa Brepols). Takie historyczno-kulturowe zainteresowania znajdują się w centrum badań mediewistycznych w ważnych europejskich ośrodkach uniwersyteckich od wielu lat, a szczególne miejsce wśród nich zajmuje zjawisko wielojęzyczności. Dlatego właśnie eROThA zawiera anotację wybranych form i struktur językowych odzwierciedlających zmianę kodów, czyli językowe świadectwa wielojęzyczności.

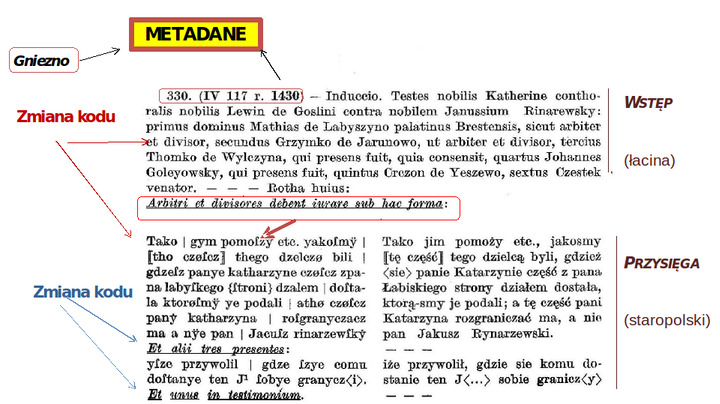

Na stronie repozytorium zmiana kodów oznaczona jest kolorami. Kolorem łaciny jest czerwony, staropolskiego zaś zielony, takie są też kolory czcionki dla wstępu i proceduralnych informacji następujących po przysiędze, która z kolei przedstawiona jest czcionką w kolorze zielonym. W bazie otagowane są przede wszystkim oznaczone przez Redaktorów „wtręty” staropolskie w łacińskich partiach tekstu, oraz „wtręty” łacińskie w przysięgach staropolskich. Dwujęzyczność ksiąg ziemskich, a konkretnie fragmentów tych ksiąg zawierających teksty przysiąg wraz z proceduralnymi ramami łacińskimi, jest zjawiskiem wielowarstwowym i złożonym. Główny nacisk anotacji wprowadzonej do materiału zaczerpniętego z wydania pada na zjawiska najmniej zbadane przez historyków języka, stanowiące novum w badaniach nad code-switching w tekstach pisanych. Są to w szczególności formy występujące na granicy języków, często o metajęzykowej naturze (o tym piszemy w Publikacje: artykuł “Metalinguistic and visual cues to code-switching in the Electronic Repository of Greater Poland Oaths”). Bardzo istotnym novum, zarówno w aspekcie anotacji, jak i w zakresie podstaw teoretycznych badań zmiany kodów w rękopisach są cechy wizualne, a dokładnie stopień przenikania się dyskursywnej i semantycznej organizacji tekstu z mis-en-page i właściwościami rękopisu odbieranymi wzrokowo (visual prosody; więcej na ten temat w Włodarczyk-Kopaczyk-Kozak (2020) Publikacje: artykuł “Multilingualism in Greater Poland court records (1386-1446): Tagging discourse boundaries and code-switching”). Anotacja repozytorium jest „lekka”: oznacza to kompromis na poziomie interpretacyjnej interwencji. Konstrukcja bazy zapewnia możliwość korzystania z bazy odbiorcom, którzy nie zajmują się wielojęzycznością, ani też w ogóle problemami badawczymi podejmowanymi przez językoznawstwo. Dlatego dla użytkowników zainteresowanych innymi aspektami tekstu źródłowego powstała także wersja bez anotacji. Dla potrzeb językoznawców badających zmianę kodów zastosowana została w repozytorium anotacja, która odpowiada tylko na wybrane przez twórców bazy bardzo precyzyjnie postawione pytania badawcze i nie stanowi całościowej interpretacji zjawiska. Format prezentacji danych umożliwia interpretację wielojęzyczności na różnych poziomach, proponując anotację w wybranym zakresie. Pliki zostały przygotowane do pobrania indywidualnie oraz zbiorczo dla każdej kolekcji w wersji zawierającej anotację (xml) oraz bez niej (txt). Ponadto pobierać można także tylko poszczególne regiony (więcej na ten temat w Jak wyszukiwać i czytać wyniki), np. wstęp łaciński.

Poniżej prezentujemy ilustrację roty nr 330 z Gniezna z wydania Kowalewicza i Kuraszkiewicza. Odpowiadającą jej prezentację na stronie można obejrzeć tutaj.

Czym jest „rota” oraz problemy selekcji

Ten podstawowy dla bazy eROThA termin definiujemy jako:

Rota opatrzona numerem i kodem lokalizacji sądu to jednostka prezentacji danych w bazie eROThA. Jako taka posiada swoje ID, a jej numeracja została zaczerpnięta z wydania drukowanego. Na przykład, najstarsza zapiska z Poznania oznaczona jest jako Pn.1. Chcąc wyświetlić tę jednostkę, należy wybrać „Poznań” spośród „Kolekcji” na stronie głównej, a następnie pierwszą pozycję z wyświetlonej listy, klikając na rozszerzone ID danej roty. Wybierając z menu „Zobacz dokument” możemy wyświetlić tekst (tj. wstęp łaciński, przysięgę staropolską, wersję ustandaryzowaną tej ostatniej oraz przypisy redaktorów) odnoszący się do pewnego fragmentu wybranego (patrz rota = sprawa w sądzie) z materiału źródłowego wraz z faksymile odpowiedniej strony rękopisu.

W opracowaniach naukowych „rota” funkcjonuje często w wąskim znaczeniu jako synonim przysięgi staropolskiej. Na platformie eROThA w opisach dotyczących projektu także używamy terminu w taki sposób, starając się jednak rozgraniczać takie jego zrozumienie od definicji podanej powyżej (rota = jednostka prezentacji).

W tytule wydania Kowalewicza i Kuraszkiewicza „rota” to nie tylko przysięga, ale także ekstrakt z rękopisu obejmujący sprawę, w której staropolska przysięga (jedna lub więcej) się znajduje. Oznacza to więc szersze ujęcie terminu, ponieważ w wypisach w wydaniu drukowanym zawarte są także informacje proceduralne (np. listy świadków, terminy rozpraw, itd.), czyli kontekst w dużej mierze nieodzowny do zrozumienia sensu przysięgi oraz identyfikacji referentów (imion, nazwisk, miejsc) w niej wymienionych. Czy rękopis jednoznacznie wskazuje jednak na początek i koniec danej sprawy? Tylko w wyjątkowych przypadkach: rota Pn.1652 jest tu idealnym przykładem pokrywania się danej sprawy ze stroną rękopisu (czyli obiektywną jednostką tworzącą strukturę księgi), ale taka sytuacja jest rzadkością. Zasadniczo rękopis nie posługuje jednoznacznymi konwencjami podziału, które wskazywałyby, gdzie poszczególne sprawy zaczynają się, a gdzie kończą. Można wprawdzie zauważyć oddzielanie poszczególnych spraw za pomocą pustych przestrzeni i wyśrodkowanych jedno- lub dwuwyrazowych linii o charakterze nagłówka, jak np. w Gn.299. W tym przypadku początek danej sprawy jest więc mało kontrowersyjny. Inaczej natomiast koniec: tu opuszczona jest łacińska część po przysiędze (opuszczenie zaznaczone przez Wydawców w tekście), mimo że kolejny blok tekstu zaznaczony przez pustą przestrzeń znajduje się dopiero po krótkim tekście łacińskim (podobnie jest w wielu przypadkach, np. Gn.60, gdzie opuszczenie nie zostało zaznaczone w wydaniu). Tak więc decyzję redaktorów, którzy wyodrębnili konkretną liczbę rot na danej stronie cechuje arbitralność [1]. Rozstrzygnięcie, w którym miejscu rozpocząć i zakończyć wypis z księgi nie jest oczywiście przypadkowe: determinuje je treść, a raczej mniej czy bardziej subiektywna interpretacja tejże przed redaktorów. I tutaj właśnie pojawia się problem dobrze znany w badaniach nad historycznymi materiałami administracyjnym i prawnymi, które z reguły są zbyt obszerne na wydanie w całości. Inną stronę tego samego problem widzimy na przykładzie rot Kos.209 i Kos.210, które znajdują się w bezpośrednim sąsiedztwie na tej samej stronie rękopisu (KosZ1, 135v). Wczytując się w treść, widzimy, że obie przysięgi (rota = przysięga) dotyczą tej samej sprawy, tyle że pierwszą z nich składa pierwszy z wymienionych w Kos.209 świadków, a drugą zawartą w Kos.210 wypowiada pięciu innych, którzy jednak nie są w tej rocie (= jednostce prezentacji) wymienieni, zostali za to wymienieni w rocie poprzedniej (Kos.209).

W ramach bazy eROThA nie było możliwe rozwiązanie problemu wynikającego z z selektywności materiału tekstowego, ponieważ jedynym sposobem byłaby edycja źródeł in extenso [2] wykraczająca znacznie poza specjalistyczne cele projektu. Fundamentalnym obszarem naszego zainteresowania jest bowiem zjawisko zmiany kodów, tj. dwujęzyczność materiału. Ponieważ język staropolski występował w księgach stosunkowo rzadko, a zmiana kodów to właśnie stykanie się ze sobą języków czy dialektów, jednostka prezentacji zbudowana w oparciu o centralną pozycję elementu wernakularnego została przejęta bezpośrednio z wydania, ponieważ odpowiada potrzebom naszych analiz. Liczba wystąpień wypowiedzi staropolskich w zapiskach prowadzonych po łacinie determinuje zakres materiału, który może być wykorzystany do analizy zmiany kodów: im więcej takich elementów, tym więcej interesującego nas materiału. Oczywiście koncepcję i ujęcie zjawiska zmiany kodów należy rozszerzyć o aspekty wizualne: taki też jest główny nurt najnowszych badań w zakresie wielojęzyczności w tekstach historycznych (więcej na temat Wielojęzyczność i zmiana kodów). Decyzji o przejęciu w eROThA wyboru wypisów dokonanego przez redaktorów wydania towarzyszy świadomość wspomnianej wyżej arbitralności, jednak udostępnienie w bazie elektronicznej faksymiliów ma na celu złagodzenie jej skutków. Udostępnienie obok wersji interpretacyjnej także wysokiej jakości skanu, umożliwia odtworzenie pełnego ko-tekstu i kontekstu staropolskiej przysięgi i otwiera materiał na korektę w zakresie selekcji fragmentów łacińskich odnoszących się do konkretnej przysięgi, wymiaru danej sprawy, czy wreszcie w kwestii fundamentalnej, tj. kryteriów klasyfikacji materiału. Tu inne są zainteresowania historyków prawa czy historyków języka tworzących różne kompendia (np. planowana nowoczesna wersja Słownika Staropolskiego; Klapper i Kołodziej 2015), atlasy (Atlas Fontium) czy słowniki (Słownik historyczno-geograficzny ziem polskich w średniowieczu pod redakcją Tomasza Jurka), a jeszcze inne językoznawców specjalizujących się np. w onomastyce [3]. Żadne wydanie tekstów źródłowych in extenso nie byłoby w stanie zaspokoić tak różnych potrzeb, dlatego duże pole do popisu mają obecnie wprawdzie selektywne i wyspecjalizowane, ale przy tym bardziej otwarte i elastyczne formy publikacji [4] umożliwiające nie tylko udostępnienie i elektroniczne zabezpieczenie bezcennych archiwaliów, ale stanowiące także próby trudnego do osiągnięcia kompromisu (Słoń i Zachara-Związek 2018: 2014-216).

Przypis 1

Problemy wydawania tekstów historycznych zostały podjęte w polskiej humanistyce na nowo w ostatnich latach w związku z próbami implementacji nowych technologii i możliwości prezentacji materiału źródłowego na platformach internetowych (np. Borowiec et al. 2017). Konkretne rozwiązania w tym zakresie proponują Autorzy portalu Atlas Fontium opartej na wielu mniejszych projektach (Słoń i Słomski 2017; Słoń i Zachara-Związek 2018). Zob. także plany stworzenia platformy Korpusy Diachroniczne Języka Polskiego (Pastuch et al. 2018).

Przypis 2

In extenso w wersji drukowanej, jak dotąd, wydane zostały poszczególne księgi ziemskie z Wielkopolski (Kaczmarczyk 1960, Jurek 1991) i jedna ze najstarszych ksiąg krakowskich (Bukowiec i Zdanek 2012). Publikacja Jurka pokazała, że redaktorzy Wielkopolskich rot sądowych nie wypisali wszystkich staropolskich fragmentów (1991: xvii), a wydanie najstarszej zachowanej księgi kaliskiej in extenso wskazało 79 nieznanych wcześniej staropolskich zapisek. Jednak w ostatnich latach znacznie większym zainteresowaniem niż księgi ziemskie cieszą się wśród historyków i historyków prawa późniejsze materiały sądów miast (np. Mikuła, Uruszczak, Karabowicz red. 2013), a w okresie 14-15 wieku, źródła praw miejskich (Mikuła 2018).

Przypis 3

„Cyfrowe udostępnianie zasobów Polskiej Akademii Nauk – Biblioteki Kórnickiej”, w co zaangażowana jest badaczka wielkopolskich ksiąg sądowych Maria Trawińska zainteresowana (w ramach projektu) onomastyką.

Przypis 4

Takie formy publikacji, a także dobry obyczaj udostępniania szerszemu gronu badaczy, czyli w formie elektronicznej, materiału źródłowego pozostają na gruncie humanistyki polskiej rzadkością (Słoń i Słomski 2017: 77, ff. 20-21).

Od wydania do repozytorium cyfrowego

Podstawą wyboru i odczytania tekstów zawartych w księgach ziemskich jest monumentalne wydanie przygotowane przez historyka i paleografa Henryka Kowalewicza oraz językoznawcę Władysława Kuraszkiewicza (1959-81).[1] Dziś publikacja ta wymaga uzupełnień, nowych interpretacji, a może nawet rewizji (zob. Uwagi paleograficzne autorstwa Olgi Makarovej), a jednak jako baza wielu przedsięwzięć badawczych [2] oraz kanonicznych źródeł wiedzy o języku staropolskim i łacinie w polskim średniowieczu, zasługuje także na otwartą i elastyczną formę publikacji cyfrowej. Dlatego też transkrybowane przez Redaktorów teksty łacińskie oraz transliterowane przysięgi polskie prezentowane są w nowoczesnym formacie kompatybilnym ze standardem TEI. Ta forma udostępnienia kierowana jest przede wszystkim do językoznawców zainteresowanych metodami korpusowymi i posługujących się narzędziami analitycznymi umożliwiającymi kwantyfikację form i struktur językowych. Format xml nie tylko zawiera ustrukturyzowaną wersje tekstową odzwierciedlającą wiele szczegółów rękopisu, ale także metadane dotyczące miejsca, daty, pisarza i źródła dokumentacji archiwalnej. Dla odbiorców specjalizujących się w innych dziedzinach nauk humanistycznych, przygotowana została uproszczona wersja tekstowa (pliki txt) części łacińskich i polskich w osobnych zbiorach, tzw. regionach (więcej na ten temat w Jak wyszukiwać i czytać wyniki). Wersje xml oraz txt pojedynczych rot i pełnych kolekcji dla poszczególnych lokalizacji można pobierać ze strony i wykorzystać jako podstawę do pracy z narzędziami do analizy języka. Repozytorium posiada także własną wyszukiwarkę, która pozwala na wyszukiwanie pojedynczych znaków, słów, ich ciągów oraz zawężanie wyników do lokalizacji, daty czy pisarza.

Przegląd cech formalnych zawartości [3] eROThA

| kolekcja | daty | teksty | ręce pisarskie |

|---|---|---|---|

| Poznań | 1386-1446 | 1653 | 57 |

| Pyzdry | 1390-1444 | 1280 | 25 |

| Kościan | 1391-1434 | 1486 [4] | 50 |

| Kalisz | 1401-1438 | 1084 | 34 |

| Gniezno | 1390-1448 | 355 | 26 |

| Konin | 1394-1432 | 491 | 18 |

| RAZEM | > 60 lat | 6349 | 210 |

Poniżej prezentujemy graf z podziałem na dekadę i liczbą tekstów dla poszczególnych sądów.

Przypis 1

Prace nad serią Wielkopolskie roty sądowe XIV-XV w. zostały podjęte w 1954 r. w Poznańskim Towarzystwie Przyjaciół Nauk dla uczczenia Tysiąclecia Państwa Polskiego. Zostały one opublikowane w pięciu tomach: akta z sądów poznańskiego (1959), pyzdrskiego (1960), kościańskiego (1967), kaliskiego (1974), gnieźnieńskiego i konińskiego (1981). Rękopisy znajdują się w zbiorach Archiwum Państwowym w Poznaniu (liczne zespoły ksiąg ziemskich) oraz w Bibliotece Kórnickiej.

Przypis 2

Krążyńska (2010); Trawińska (2009); Słoboda (2005), (2012). Temat wielojęzyczności w księgach ziemskich z Wielkopolski podejmowany był przez Trawińską (2014); Kuźmickiego (2013, 2015) oraz Borowiec (2013).

Przypis 3

Elektroniczna forma publikacji umożliwia modyfikację treści (tj. korektę, jeśli zachodzi potrzeba), a elastyczna architektura repozytorium pozwala na jej uzupełnianie i dodawanie.

Przypis 4

Roty w wersji brudno- i czystopisowej liczone jeden raz.

Źródło drukowane:

Kowalewicz, Henryk & Władysław Kuraszkiewicz (eds.). 1959-1981, Wielkopolskie roty sądowe XIV–XV wieku, t.1, Roty poznańskie, t. 2, Roty pyzdrskie, t. 3, Roty kościańskie, t. 4, Roty kaliskie, t. 5, A, Roty gnieźnieńskie B, Roty konińskie. Warszawa, Poznań, Wrocław, Kraków & Gdańsk: Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe.

Jak wyszukiwać i czytać wyniki

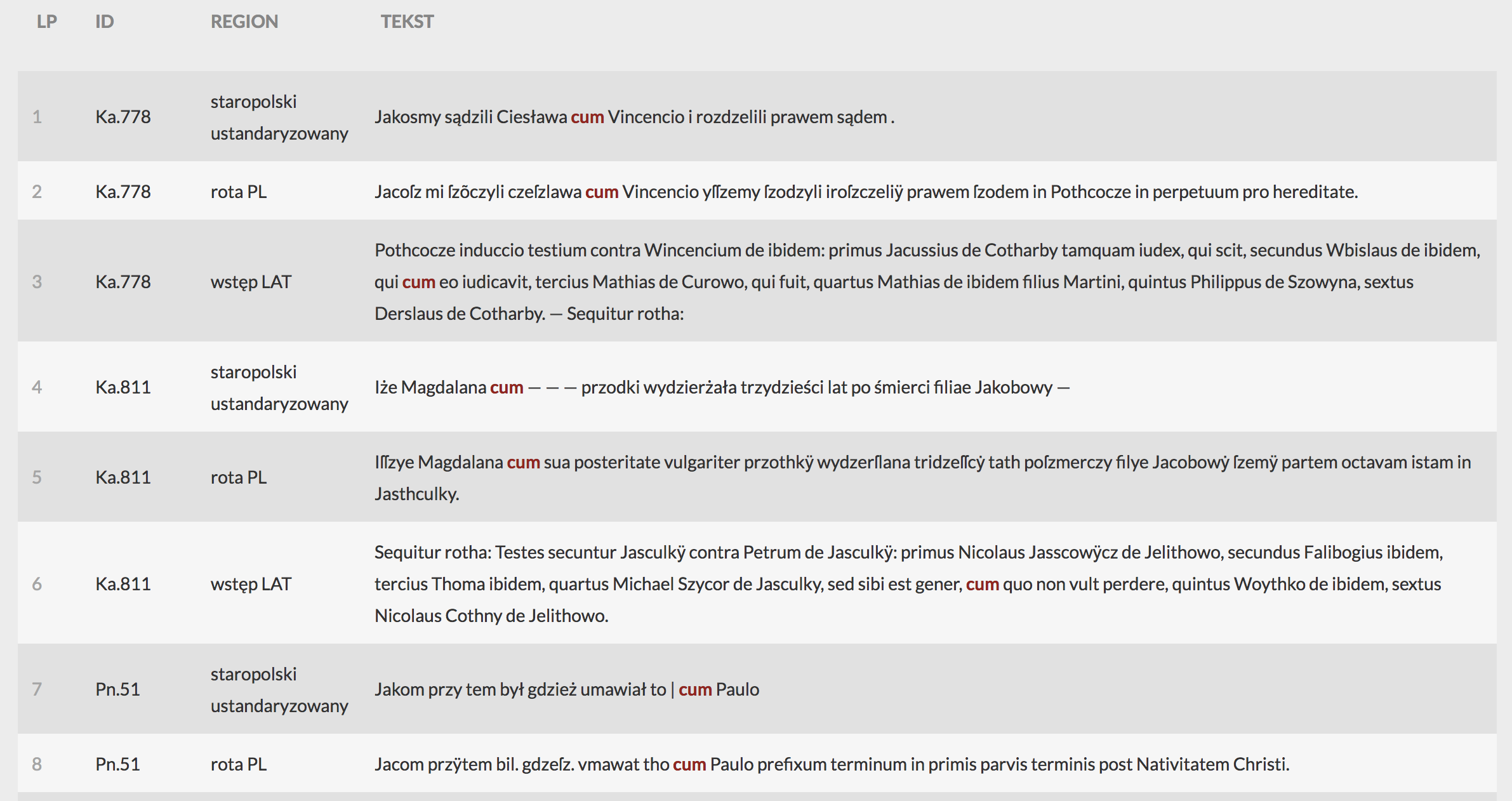

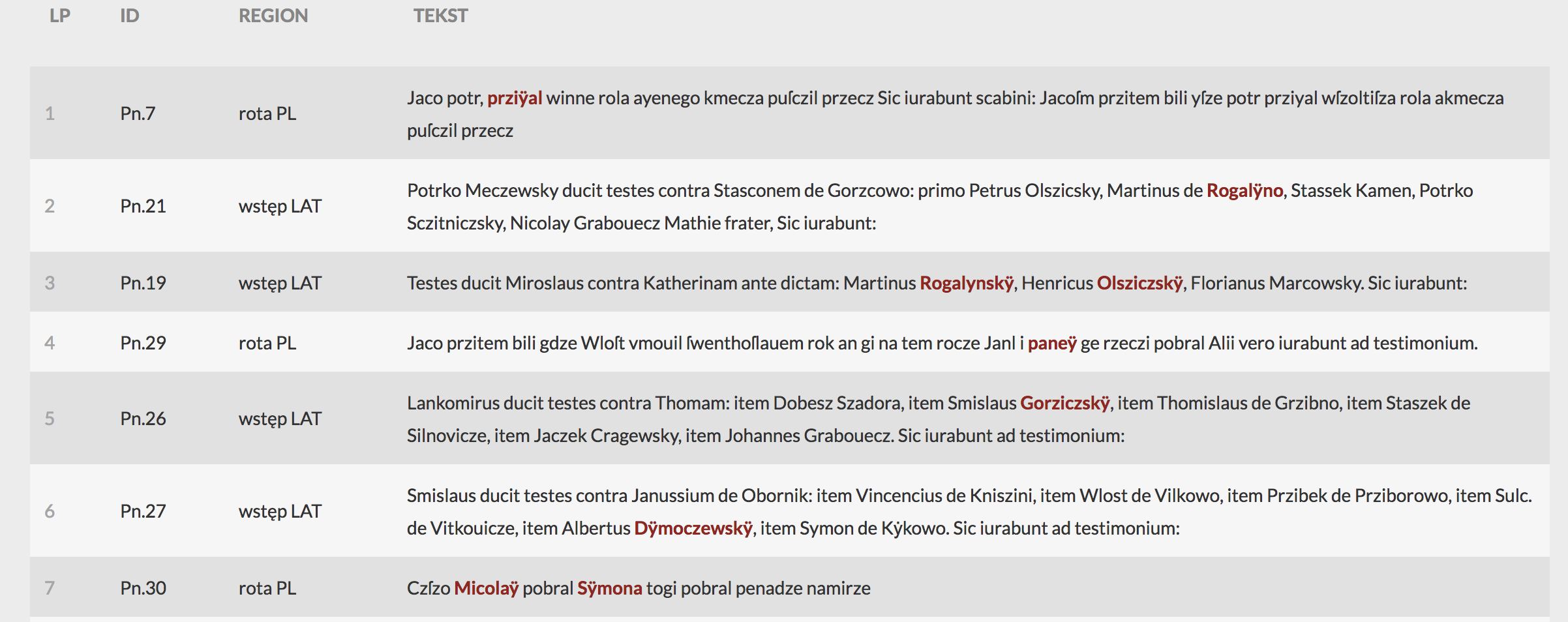

Możliwe jest wyszukiwanie znaków, słów oraz ich ciągów. Okienko znaków staropolskich umożliwia wstawienie symboli użytych głównie w transliteracji staropolskiej. Jeśli chcemy wyszukać konkretne słowo, np. cum, i wszystkie jego występowania, wpisujemy je do wyszukiwarki. Otrzymujemy następujący widok:

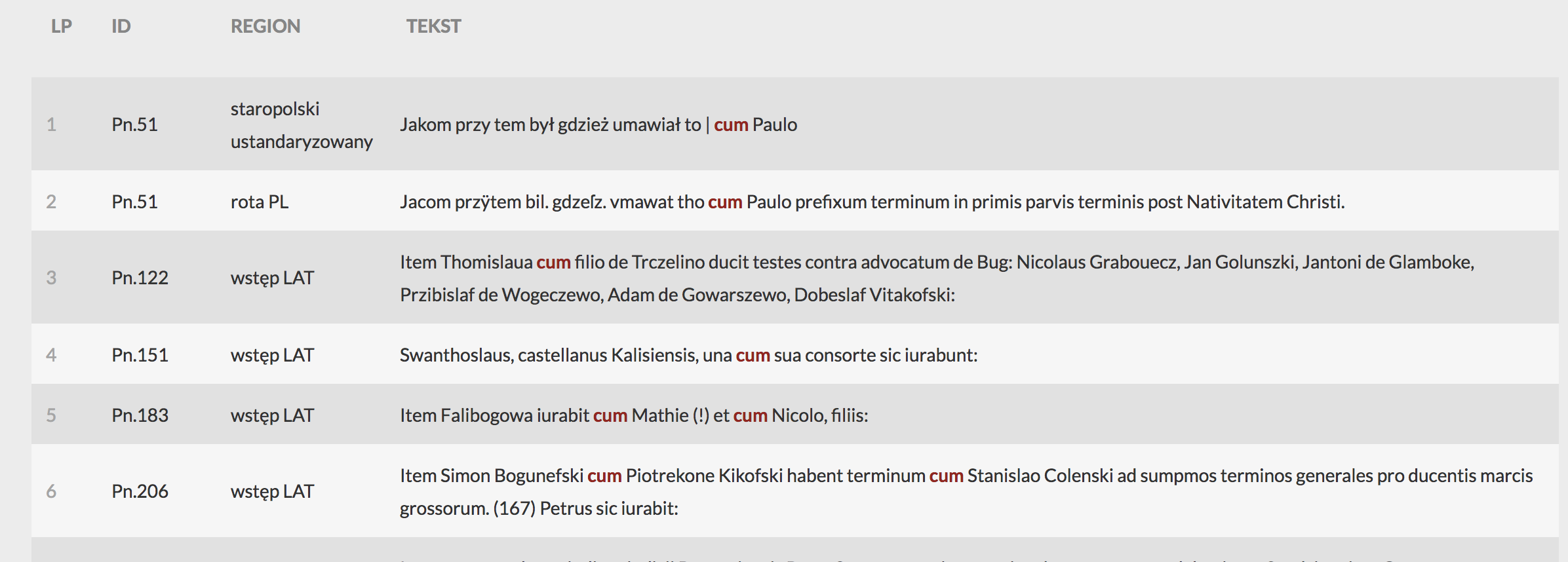

Teraz możemy wybrać opcję Pokaż lub Pobierz pełne wyniki wraz z kontekstem. W drugim przypadku pobrany zostanie plik tsv, który może służyć do dalszej obróbki w programie excel oraz za pomocą narzędzi do analizy korpusowej.

Jeśli zdecydujemy się wyświetlić wyniki, w nowym oknie otrzymamy tabelę z numeracją, opisem roty w postaci skróconej w kolumnie ID (np. Pn.1, oznacza rotę nr 1 z Poznania), regionem występowania w kolumnie REGION (tj. wstęp łaciński, rota staropolska lub wersja ustandaryzowana, oznaczone odpowiednio jako wstęp LAT, rota PL, staropolski ustandaryzowany) oraz oznaczone czerwoną czcionką wyszukiwane słowo wraz z kontekstem.

Przed pobraniem możemy wyniki posortować wg. ID, wówczas wyświetli nam się lista wyników wg. miejsca i kolejności:

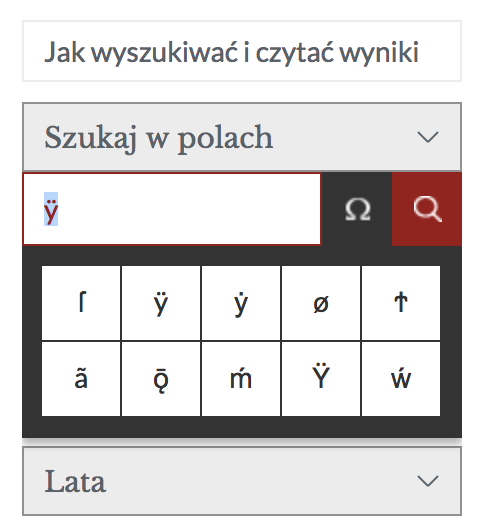

Wyszukiwarka pozwala także na znajdowanie ciągu znaków wewnątrz słów jeśli, na przykład, interesuje nas dystrybucja grafemu „ÿ”. W tym celu należy otworzyć okienko symboli użytych w transliteracji staropolskiej, klikając na symbol omega:

Możemy w ten sposób przywołać wszystkie wyrazy zawierające ten znak wpisując go pomiędzy *ÿ*, będzie ich ponad 2000. Po posortowaniu wyświetlimy taki widok:

Wyniki można teraz zawęzić do poszczególnych Kolekcji, Pisarzy i Dat. Według tych metadanych można także przeglądać poszczególne kolekcje. W tym celu należy najpierw kliknąć na wybraną lokalizację, np. Poznań. Po wyświetleniu wszystkich rot dla tej kolekcji, można także wybrać konkretnego pisarza i wyświetlić listę tylko tych rot, które zostały przez niego spisane.

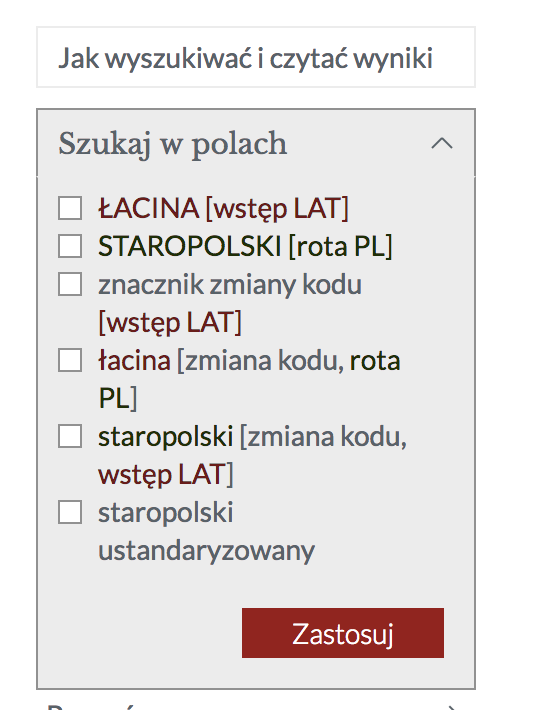

Wyszukiwanie pod kątem zmiany kodów odbywa się za pomocą zawężania regionów wyszukiwania:

Możemy zatem wyszukać znak *ÿ* lub słowo cum tylko we wstępie łacińskim, czy rocie staropolskiej, w obu tych częściach, ale też w pozostałych regionach istotnych dla oznaczenia zmiany kodów. Jeśli wybierzemy tylko opcję „łacina [zmiana kodu, rota PL]” otrzymamy tylko wystąpienia słowa cum w rocie PL:

Daną rotę można wywołać klikając na jej szczegółowe ID. Po wybraniu roty, po prawej stronie otrzymamy opcję „Zobacz dokument”. Po jej kliknięciu możemy przeglądać faksymile i wersje tekstowe. W okienku przeglądarki pojawi się wówczas adres danej roty, zakodowany jej ID. Dla roty nr 3 z Pyzdr będzie to: https://rotha.ehum.psnc.pl/breeze/Py.3.

Teraz, znając skróty do poszczególnych kolekcji, możemy przechodzić pomiędzy rotami, zmieniając tylko ID po ostatnim ukośniku. Np. po wpisaniu Pn.3 w miejsce Py.3, otrzymamy stronę wstępną roty nr 3 z Poznania. Wykaz skrótów używanych w ID rot:

- Poznań - Pn

- Pyzdry - Py

- Kościan - Kos

- Kalisz - Ka

- Gniezno - Gn

- Konin - Kon

Kontekst instytucjonalny

Proces sądowy obejmuje szereg czynności prawnych, w przypadku sądów ziemskich z przełomu 14 i 15 wieku regulowanych zwyczajowym prawem ziemskim obejmującym ok. 8-12% społeczeństwa, tj. szlachtę (Uruszczak 2015: 71-72; 78-81). Oczywiście proces sądowy w średniowieczu odbiegał znacząco od funkcjonowania współczesnych nam instytucji. Sądy ziemskie na przykład nie miały stałej siedziby. Zbierały się w wyznaczone terminy (kadencje sądu) zwane rokami sądowymi, które odbywały się cztery razy do roku w ustalonych miejscowościach – stolicach powiatów. Roczkami określano kadencje mniejszej ważności (definicje pochodzą z Doroszewski; SXVI t. XXXV: 300), te odbywać mogły się nawet co 2 tygodnie. W ramach roków odbywały się procesy prawne – tzw. rozprawy (czy sprawy sądowe), którym to terminem w staropolszczyźnie nazywano „rozpatrywanie, rozstrzyganie sporu przez sąd” (Sstp t. VII, s. 557). Sąd ziemski zajmował się zwłaszcza sprawami cywilnymi, a przede wszystkim majątkowymi (dziedziczenie, przekazywanie, odebranie, sprzedaż i inne czynności prawne dotyczące dóbr). Do jurysdykcji sądu ziemskiego należało także rozstrzyganie spraw kryminalnych: zabójstwa, gwałty, kradzieże itp. W skład sądu ziemskiego dla danego powiatu wchodzili sędzia, podsędek i pisarz [1] wybierani pod czas sejmików i zatwierdzani przez króla (Gąsiorowski 1970: 51-55), choć z powodu często odbywanych roków zwykle reprezentowali ich zastępcy. Na roczkach w Wielkopolsce zasiadali także przedstawiciele podkomorzego, chorążego, wojewody i burgrabiego (Gąsiorowski 1970: 50).

Pisarze

Osoby prowadzące zapiski w sądach ziemskich w interesującym nas okresie rzadko znamy z nazwiska. Niejasne są także szczegóły ich przygotowania zawodowego ani wykształcenia. Redaktorzy wydania Wielkopolskich rot sądowych twierdzą, że „sztuki zapisywania tekstów polskich musiano uczyć już dawniej w szkołach lub wprost w kancelarii sądowej” (Kowalewicz i Kuraszkiewicz 1959: 18). Poziom i forma takiej edukacji nie jest oczywista: przed połową XV w. mogły to być bezpośrednio kancelarie (również funkcjonujące przy szkołach parafialnych), gdyż już od połowy XV w. rozpowszechniły się szkoły parafialne, w których przede wszystkim uczono czytania i pisania (por. Bartoszewicz 2001: 8-9). W kancelariach sądowych XV w. mogły być zatrudnione również osoby mające wykształcenie uniwersyteckie (Bartoszewicz 2001: 16), choć obecnie badacze skłaniają się raczej ku mniej zaawansowanym stopniom wykształcenia (Bartoszewicz 2014: 179). Brak danych na temat pisarzy w rotach wielkopolskich świadczy o tym, że w wieku XIV-XV byli to urzędnicy niższego szczebla (Gąsiorowski 1970: 55-56; 78-79). Historycy prawa zwracają uwagę na to, że powiatowy pisarz sądowy miał pomocników – podpisków. Zatem osoby spisujące treści zawarte później w księgach nie miał wpływu na proces sądowy, a do ich obowiązków wchodziło czuwanie nad właściwym kształtem dokumentacji, czyli zapisek (por. Moniuszko 2013: 175). Jednocześnie pisarz sądowy mianowany przez króla mógł wcale nie wykonywać czynności wpisywania spraw sądowych do ksiąg, a będąc już urzędnikiem wyższej rangi, był obecny na głównych posiedzeniach sądu razem z sędzią i podsędkiem. Procedury związane z prowadzeniem dokumentacji urzędowej w średniowiecznych księgach ziemskich są wciąż mało znane. Najwcześniejsze zapiski mają charakter brulionowy w formacie dutki (tzw. folio fracto, czyli złożony na pół wg. dłuższego boku arkusz w przybliżeniu odpowiadający A4) (Jurek 1991: III-IV; Bukowski i Zdanek 2012: 8). O ile w wieku 16 i 17, mamy dowody na wzrost rangi prawnej wpisu do ksiąg, także ziemskich, a sama czynność wpisywania sprawy była nazywana terminami łacińskimi: actico, connoto, ingroso, lub w postaci adaptowanej aktykować, konnotować, ingrosować (por. Makarowa 2017: 106-107), terminy te nie występują w bazie eROThA. Księgi ziemskie stanowią zatem raczej podstawę wystawiania dokumentów zaświadczających stan prawny np. przez sędziów, niż stanowią same w sobie dokumenty o takiej mocy (por. Gąsiorowski 1970: 54-55; Jurek 2002: 16).

Co oznaczają liczne przekreślenia dużych partii tekstu?

Zapiski podlegały korekcie oraz były kopiowane prawdopodobnie ze skrawków papieru na karty formatu dutki, czasem z jednej księgi do innej. Znany jest jeden przypadek prowadzenia księgi brudnopisowej i zachowania obu wersji zapisek (Kościan, księga V z lat 1416-1425) Prezentacja rot koscianskich, ale taka praktyka mogła być stosowana szerzej. Skreślanie całych partii tekstu ma ważkie znaczenie proceduralne i prawne. W księgach ziemskich wielkopolskich (Jurek 1991: x; i nie tylko: por. Bukowski i Zdanek 2012: 14) praktyka całkowitego przekreślenia poszczególnych rot oznaczała ich prawne unieważnienie. Czynność ta była zwana zniesieniem, kasowaniem lub sterminowaniem (Makarova 2017: 108). Skreślenia obejmują całe roty, jak i ich części: na przykład w zapiskach kaliskich często zdarzają się skreślenia nazwisk świadków jednej ze stron procesu sądowego (Ka.218, Ka.200, Ka.595). Przekreślenie którejś z części zapiski nie musi jednak zawsze równać się jej proceduralnemu unieważnieniu. Na przykład w rocie Ka.627 została przekreślona część protokołu, w której jest opisana treść sprawy, co może być konsekwencją pomyłki pisarza przy wpisywaniu tej roty.

Rola łaciny

Językowy wizerunek kancelarii sądowych zmieniał się w historii rozwoju sądów i sądownictwa nie tylko w Wielkopolsce, ale oczywiście także szerzej w całej Europie. W średniowieczu najważniejsza była tu łacina, zaświadczone są w pewnym stopniu także języki „rodzime”, czyli wernakularne. W wielu regionach polskojęzycznych i sąsiednich istotną rolę pełnił także język niemiecki (Śląsk, Bohemia, Kraków; Adamska 2006: 355). Samsonowicz uważa, że pisana łacina stanowiła lingua franca dla zróżnicowanego etnicznie i rozwarstwionego społeczeństwa i platformę komunikacyjną między: „Polakami i Niemcami, świeckimi i duchownymi, miejscowymi i Żydami, chłopstwem, rycerstwem i mieszczaństwem” (1993: 157).

Rozpowszechnianie się łaciny w okresie późnego średniowiecza wiązało się z rozwojem szkół i oświaty humanistycznej, ale była ona lepiej znana raczej tylko wąskiej grupie duchownych, wyższym rangą urzędnikom oraz kupcom (por. Bartoszewicz 2014: 179; Adamska 2013: 334-35). Niemniej jednak miała charakter języka urzędowego, co wynika niezbicie z charakteru zapisów w księgach sądów ziemskich, miejskich, a także kancelarii królewskich, bez względu na to, w jakim języku prowadzono ustne czynności urzędowe i prawne (por. Bedos-Rezak 1996). Zatem w piśmie użycie języków wernakularnych zostało ograniczone do funkcji pomocniczej (Doležalová 2015: 161; por. Adamska 2013 w odniesieniu do materiałów polskich, czeskich i węgierskich). W księgach sądowych, o których jest tu mowa, ta sytuacja uległa zmianie nie w kierunku wernakularyzacji, jak miało to miejsce w innych miejscach w szczególnie w Europie Zachodniej (ale także np. w Czechach; Adamska 2013: 356), a w kierunku całkowitej dominacji łaciny. I tak: „[n]ajdawniejsze zapiski sądowe sięgają ostatniej ćwierci w. XIV i ciągną się odtąd nieprzerwanie poprzez cały w. XV i XVI, z wolna ustępując potem miejsca po łacinie spisywanym protokołom spraw sądowych” (Lehr-Spławiński 1978: 164-165). Badacz zaznacza także, że spisywane w całości po polsku zapiski stanowiły raczej wyjątki, z reguły polskie elementy w zapiskach sądowych stanowiły tylko krótkie notatki, zeznania świadków i teksty przysiąg (pierwsze staropolskie roty w księgach z Poznaniu pochodzą z 1386 r.) ze względu na konieczność zachowania oryginalnej formy i treści oraz wartość dowodową ustnego rytuału oczyszczenia.

Jak wynika z zestawień przedstawionych w wydaniu Kowalewicza i Kuraszkiewicza (np. 1959: 10; 1960: 6; 1981: 7), roty polskie zaczęły znikać z ksiąg ziemskich w sądach wielkopolskich mniej więcej w okresie 1430-1440. Najwcześniej łacina całkiem zastępuje język polski w zapiskach konińskich (1432 r.), najpóźniej – w gnieźnieńskich (1448 r.). Zachowanie zaś w rotach łacińskich poszczególnych ksiąg formuł wstępnych i końcowych spisywanych po polsku (tako mi pomoży Bog, lub końcowych: Jako to świadczą) świadczy o dalszym przeprowadzaniu dowodu podczas rozpraw sądowych w tym języku (Kowalewicz i Kuraszkiewicz: 1967: 5).

Przypis 1

Uruszczak (2015) podaje łacińskie odpowiedniki nazw urzędów administracji królewskiej i książęcej.

Prezentacja rot kościańskich

Roty kościańskie uznawane są przez badaczy za przypadek specjalny, ponieważ ich część (370 rot) zachowała w dwóch wersjach: brudno- i czystopisowej. Księgą brudnopisową jest księga V, zaś wersje czystopisowe znajdują się w księgach IV, VI, VII i VIII (Kowalewicz i Kuraszkiewicz 1967: 7-8; 22-25; 27-30). Z punktu widzenia językoznawstwa wersje brudnopisowe są niezwykle ciekawe, gdyż zawierają wiele poprawek pisarskich, dając wgląd w sposób ich redakcji. Dlatego też Kowalewicz i Kuraszkiewicz przyjęli te właśnie wersje za podstawę prezentacji, mimo że prezentacja tekstu takich "podwójnych" rot stanowi duże wyzwanie. Wydawcy rot wielkopolskich zdecydowali się na przedstawienie ich tekstów (tj. brudnopisu i odpowiadającej mu wersji czystopisowej) na 3 sposoby:

- przypisy odnoszące się do poszczególnych słów: najczęściej obejmują poprawki wprowadzone przed przepisaniem na czysto (skreślenia, zastąpienia pojedynczych słów czy wyrażeń, uzupełnienia), np.: Kos.767, Kos.975.

- przypisy odnoszące się do partii tekstu - zawierają bardziej skomplikowane interwencje pisarskie, np.: Kos.971, Kos.973.

- osobna rota dla wersji brudno- i czystopisowej - rzadziej wersja ostateczna odbiega tak daleko od wersji brudnopisowej, że przedstawiona jest jako osobna rota, np.: Kos.771 i Kos.771a.

Poza nielicznymi wyjątkami, w repozytorium eROThA prezentacja "podwójnych" rot kościańskich została ograniczona do wersji brudnopisowej, a przypisy, o których mowa w punkcie a. i b. powyżej, zostały usunięte. [1] Natomiast przypadki opisane w punkcie c., tj. obie pełne wersje w osobnych rotach opatrzonych numerami (jak Kos.771 i Kos.771a powyżej), prezentowane są dokładnie tak, jak w wydaniu. Decyzja o opuszczeniu nieraz bardzo długich list przypisów podyktowana została wymaganiami wyszukiwarki i małą przejrzystością tej formy prezentacji. Zmiany i interwencje pisarskie pomiędzy brudnopisem a czystopisem wymagają osobnego metodologicznego opracowania, a ograniczenie ich prezentacji do przypisów nie odpowiada ich zakresowi ani nie stanowi uporządkowanego przyczynku do ich kategoryzacji.

Mimo, że w repozytorium zrezygnowano z przypisów oznaczających zmiany pomiędzy brudno- a czystopisem, to wersję podstawową tekstu, tj. brudnopis danej roty opatrzono skanami zarówno z brudno- jak i z czystopisu (np.: Kos.975). Prezentacja taka daje wgląd w rękopis, umożliwiając zarówno rewizję materiału na poziomie paleografii, jak i otwiera możliwości nowych konceptualizacji zmian pisarskich.

Przypis 1

Przykładem może być tu rota Kos.1117. Należy zwrócić uwagę, że wyświetlając tę i inne takie roty, w górnym pasku nad oznaczonym kolorem czerwonym i numerem PISARZA mamy odniesienie do zasobu archiwalnego. Odniesienie to wskazuje źródło brudnopisowe (np.: w Kos.1117 jest to Księga ziemska 5, Karta 514v). Źródło czystopisowe widzimy na platformie w kolejnych skanach, a informacja na jego temat widoczna jest w wersji TEI pliku (można ją znaleźć także tutaj).

Literatura

- Adamska, Anna. 2013. Latin and three vernaculars in East Central Europe from the point of view of the history of social communication. 325–364. In Mary Garrison, Aprad Órban & Marco Mostert (eds.), Spoken and written language. Relations between Latin and the vernacular languages in the earlier Middle Ages. Turnhout: Brepols.

- Bartoszewicz, Agnieszka. 2001. Litterati burghers in Polish late medieval towns. Acta Poloniae Historica 83: 5–26.

- Bartoszewicz, Agnieszka. 2014. Urban literacy in small Polish towns and the process of 'modernisation' of society in later Middle Ages. 149–183. In Marco Mostert & Anna Adamska (eds.), Writing and administration of mediaeval towns. Turnhout: Brepols.

- Bartoszewicz, Agnieszka. 2017. Urban literacy in late medieval Poland. Turnhout: Brepols.

- Bedos-Rezak, Brigitte. 1996. Secular administration. 195–229. In F.A.C. Mantello & A.G. Rigg (eds.), Medieval Latin. An Introduction and bibliographical guide. Washington: The Catholic University of America Press.

- Borowiec, Karolina. 2013. Wokół rot kościańskich. O specyficznej sytuacji edytorskiej [Kościan court oaths. On the editorial status]. Kwartalnik Językoznawczy 4: 2–11.

- Borowiec, Karolina, Dorota Masłej, Tomasz Mika & Dorota Rojszczak-Robińska. 2017. Jak wydawać teksty dawne [How to edit old texts]. Poznań: Wydawnictwo Rys.

- Bukowski, Waldemar & Maciej Zdanek. 2012. Księga ziemska krakowska 2 [Cracow land book 2]. 1394-1397. Warszawa: Instytut Historii PAN.

- Doležalová, Lucie. 2015. Multilingualism and late medieval manuscript culture. 160–180. In Michael Johnston & Michael Van Dussen (eds.), The medieval manuscript book: Cultural approaches. (Cambridge Studies in Medieval Literature). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9781107588851.009

- Doroszewski, Witold (ed.). 1958–1969. Słownik języka polskiego (SJP) [The dictionary of the Polish language]. Warszawa: PWN. http://sjp.pwn.pl/doroszewski.

- Gąsiorowski, Antoni. 1970. Urzędnicy zarządu lokalnego w późnośredniowiecznej Wielkopolsce [Local administrative officials in late medieval Greater Poland]. Poznań: Poznańskie Towarzystwo Przyjaciół Nauk.

- Jurek, Tomasz (ed.). 1991. Księga ziemska kaliska 1400-1409 [Kalisz land court book 1400-1409]. Poznań: Poznańskie Towarzystwo Przyjaciół Nauk.

- Jurek, Tomasz. 2002. Stanowisko dokumentu w średniowiecznej Polsce [The status of the document in medieval Poland]. Studia Źródłoznawcze 50: 1–18.

- Jurek, Tomasz (ed.). 2018. Słownik historyczno-geograficzny ziem polskich w średniowieczu. Edycja elektroniczna [Historical-geographiccal dictionary of Polish lands in the Middle Ages. Electronic edition.] http://www.slownik.ihpan.edu.pl

- Kaczmarczyk, Kazimierz (ed.). 1960. Księga ziemska poznańska 1400-1407 [Poznań land book 1400-1407]. Poznań: Poznańskie Towarzystwo Przyjaciół Nauk.

- Klapper, Magdalena & Dorota Kołodziej. 2015. Elektroniczny Tezaurus Rozproszonego Słownictwa Staropolskiego do 1500 roku. Perspektywy i problemy [Digital Thesaurus of Scattered Old Polish Lexis until 1500. Prospects and issues]. Polonica 35: 87-101.

- Kowalewicz, Henryk & Władysław Kuraszkiewicz (eds.). 1959-1981, Wielkopolskie roty sądowe XIV–XV wieku [The Greater Poland court oaths of the 14th-15th century], vol. 1, Roty poznańskie [The Poznań oaths], vol. 2, Roty pyzdrskie [The Pyzdry oaths], vol. 3, Roty kościańskie [The Kościan oaths], vol. 4, Roty kaliskie [The Kalisz oaths], vol. 5, A, Roty gnieźnieńskie [The Gniezno oaths], B, Roty konińskie [The Konin oaths]. Warszawa, Poznań, Wrocław, Kraków & Gdańsk: Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe.

- Krążyńska, Zdzisława. 2010. Średniowieczne techniki rozbudowywania zdań (na przykładzie wielkopolskich rot sądowych) [Medieval sentence complementation, on the basis of Greater Poland court oaths]. Kwartalnik Językoznawczy 3-4: 1–16.

- Kuraszkiewicz, Władysław. 1986. Brudnopisy i czystopisy rot kościańskich [Drafts and clean copies of Koscian oaths]. In Władysław Kuraszkiewicz (eds.), Polski język literacki. Studia nad historią i strukturą [Polish literary language: Studies in history and structure]. Warszawa-Poznań: Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe.

- Kuźmicki, Marcin. 2013. Współistnienie języków w rotach przysiąg sądowych [Co-existence of languages in court oaths]. Slavia Occidentalis 70 (1): 75–85.

- Kuźmicki, Marcin. 2015. Wydanie wielkopolskich rot sądowych w świetle najnowszych ustaleń badawczych [The edition of Greater Poland court oaths in the light of current research]. LingVaria 20: 205–219.

- Lehr-Spławiński, Tadeusz. 1978. Język polski: Pochodzenie, powstanie, rozwój [The Polish language: Origins, emergence and development]. Warszawa: Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe.

- Makarova, Olga. 2017. Leksyka prawnicza w polskich zapiskach sądowych z Ukrainy (XVI i XVII wiek) [Legal lexicon in the Polish court records from Ukraine (16th and 17th centuries)]. Warszawa: Wydawnictwo DiG.

- Mikuła, Maciej, Wacław Uruszczak & Anna Karabowicz (red.). 2013. Księga kryminalna miasta Krakowa z lat 1554-1625 [Criminal records of Kraków city for 1554-1625]. Kraków: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego.

- Mikuła, Maciej. 2018. Source editions of municipal law in Poland (14th–16th century): A proposal for an Electronic Metaedition of Normative Source Material. Krakowskie Studia z Historii Państwa i Prawa 12 (5): 85–110. doi:10.4467/20844131KS.18.033.9121

- Moniuszko, Adam. 2014. Rejestry nieruchomości (księgi gruntowe) w dawnej Polsce – czy naprawdę istniały? [The estate registers in historical Poland – did they really exist?] Czasopismo Prawno-Historyczne LXVI (1): 451–475.

- Pastuch, Magdalena, Beata Duda, Karolina Lisczyk, Barbara Mitrenga, Joanna Przyklenk & Katarzyna Sujkowska-Sobisz. 2018. Digital Humanities in Poland from the perspective of the historical linguist of the Polish language: Achievements, needs, demands. Digital Scholarship in the Humanities 33 (4): 857–873. https://doi.org/10.1093/llc/fqy008

- Samsonowicz, Henryk. 1993. Roty sądowe w Polsce jako źródło do dziejów kultury [Court oaths in Poland as a resource for cultural history]. 476–484. In Teresa Michałowska (ed.), Literatura i kultura późnego średniowiecza [The literature and culture of the late Middle Ages]. Warszawa: Instytut Badań Literackich.

- Słoboda, Agnieszka. 2012. Liczebnik w grupie nominalnej średniowiecznej polszczyzny. Semantyka i składnia [The numeral in the nominal phrase in medieval Polish. Semantics and syntax]. Poznań: Wydawnictwo Rys.

- Słoń, Marek & Michał Słomski. 2017. Edycje cyfrowe źródeł historycznych [Digital editions of historical sources]. 65–85. In Karolina Borowiec et al. (eds.), Jak wydawać teksty dawne [How to edit old texts]. Poznań: Wydawnictwo Rys.

- Słoń, Marek & Urszula Zachara-Związek. 2018. The court records of Wschowa (1495–1526). Digital edition. Special issue of Studia Geohistorica (Rocznik historyczno-geograficzny) 6: 206–220.

- Trawińska, Maria. 2009. Cechy dialektalne wielkopolskich rot sądowych w świetle badań nad rękopisem poznańskiej księgi ziemskiej [Dialect features of the Greater Poland court oaths: The analysis of the Poznań land book manuscript]. Prace Filologiczne LVI: 345–360.

- Trawińska, Maria. 2014. Rękopis najstarszej poznańskiej księgi ziemskiej (1386-1400) [The manuscript of the oldest Poznań land court book (1386-1400)]. Warszawa & Poznań: Wydawnictwo Rys.

- Uruszczak, Wacław. 2015. Historia państwa i prawa polskiego. T. 1: 966-1795 [The history of the Polish state and law. Vol. 1: 966-1795]. 3rd edition. Warszawa: Wolters Kluwer.

Publikacje

Poniżej prezentujemy listę publikacji oraz wystąpień konferencyjnych. Treści te, w odróżnieniu od popularyzatorskiego charakteru opisów znajdujących się w pozostałych zakładkach, zawierają specjalistyczne analizy z zakresu językoznawstwa historycznego. Są formą rozpowszechniania informacji o projekcie i wyników badań, a także wnoszą do językoznawstwa historycznego analizy zmiany kodów wykonane w oparciu bazę eROThA. Powstałe w toku analiz nowe teoretyczne i metodologiczne ramy mogą zostać zastosowane w dalszych badaniach specjalistycznych tekstów wielojęzycznych z okresu średniowiecza i wczesnej nowożytności, a także późniejszych dokumentów rękopiśmiennych. Wkład, jaki badania na bazie eROThA wnoszą do dyscypliny językoznawstwa historycznego wychodzi poza obszar relacji między łaciną a językiem staropolskim, a uwzględnienie w zaproponowanym przez zespół badawczy eROThA ujęciu cech wizualnych nadaje wynikom badań wymiar uniwersalny i stanowi o jego innowacyjności. Treści załączonych dokumentów służą wyżej wymienionym celom i nie mogą być powielane bez odpowiednich odniesień.

Opublikowane

- Kopaczyk, J., M. Włodarczyk & E. Adamczyk. 2016. Medieval multilingualism in Poland: Creating a corpus of Greater Poland court Oaths (ROThA). Studia Anglica Posnaniensia 51 (3), 9-35.

- Włodarczyk, M. Kopaczyk J. & M. Kozak. 2020. Multilingualism in Greater Poland court records (1386-1446): Tagging discourse boundaries and code-switching (Short corpus report). Corpora 15 (3) (AOP).

- Strona projektu: https://rotha.ehum.psnc.pl

Złożone (w recenzji)

- Włodarczyk, M., E. Adamczyk & Olga Makarova. (złożone do Reihe „IVS SAXONICO-MAIDEBVRGENSE IN ORIENTE“, De Gruyter). Code-switching and literalisation in provincial court books (libri terrestres) – the Electronic Repository of Greater Poland Oaths (1386-1444)

- Włodarczyk, M. & E. Adamczyk. (złożone do Zeitschrift fur Slavische Philologie Reihe). Constraints on embedded multilingual practices in the Electronic Repository of Greater Poland Oaths (1386-1446)

W przygotowaniu

- Włodarczyk, M. & E. Adamczyk. Metalinguistic and visual cues to the co-occurrence of Latin and Old Polish in the Electronic Repository of Greater Poland Oaths (1386-1446, eROThA).

- Tyrkkö, J., M. Włodarczyk, J. Kopaczyk & E. Adamczyk. (red.). Multilingualism meets multimodality: Historical and modern contexts. Tematyczny tom zbiorowy.

- Włodarczyk, M. & E. Adamczyk. Towards a taxonomy of historical code-switching: Core and periphery in the Electronic Repository of Greater Poland Oaths (1386-1446, eROThA).

- Włodarczyk, M. Scribal agency and visual code on the bilingual page in the Electronic Repository of Greater Poland Oaths (eROThA).

Wystąpienia konferencyjne

- Kopaczyk, J., M. Włodarczyk & E. Adamczyk. 2019. Multilingualism meets multimodality: problems and solutions for historical corpora. Keynote address at Historical Corpora and Variation Conference, University of Cagliari, Italy.

- Włodarczyk, M., J. Kopaczyk & E. Adamczyk. 2018. Flagging the language boundary in the Electronic Repository of Greater Poland Oaths (1386-1444). Prezentacja wygłoszona na zaproszenie VS SAXONICO-MAIDEBVRGENSE IN ORIENTE „Das sächsisch-magdeburgische Recht als kulturelles Bindeglied zwischen den Rechtsordnungen Ost- und Mitteleuropas“ Bestandsaufnahme und Perspektiven der Forschung. Sächsische Akademie der Wissenschaften zu Leipzig.

- Włodarczyk, M., E. Adamczyk & J. Kopaczyk. 2018. Code-switching on the page in the Electronic Repository of Greater Poland Oaths (1386-1444). Prezentacja wygłoszona na sesji tematycznej pt. “Multilingualism and multimodality” podczas konferencji 48th Poznań Linguistic Meeting. Poznań.

- Włodarczyk, M., J. Kopaczyk & E. Adamczyk. 2018. Crossing the language and discourse boundaries in the Electronic Repository of Greater Poland Oaths, 1386-1444 (ROThA). Prezentacja wygłoszona na zaproszenie: Understanding multilingual sermons of Middle Ages, Vienna, Austrian Academy of Sciences.

- Włodarczyk, M., J. Kopaczyk & E. Adamczyk. 2017. Visual code-switching in the Electronic Repository of Greater Poland Oaths 1386-1444 (ROThA). Prezentacja wygłoszona na konferencji: Monolingual histories – Multilingual practices. Issues in historical language contact, Ghent University.

- Włodarczyk, M. & M. Kozak. 2017. Wielojęzyczność w średniowiecznej Wielkopolsce: Digitalizacja wielkopolskich rot sądowych (projekt ROThA). Prezentacja wygłoszona na: IV Konferencji DARIAH-PL: Humanistyka cyfrowa a instytucje dziedzictwa, Wrocław.

- Włodarczyk, M., J. Kopaczyk & E. Adamczyk. 2016. Towards a framework for analysing code-switching in the Electronic Repository of Greater Poland Oaths, 1386-1444 (ROThA). Prezentacja wygłoszona na konferencji: Historical Sociolinguistics and Socio-Cultural Change, University of Helsinki.

- Kopaczyk, J., M. Włodarczyk & E. Adamczyk. 2016. Electronic Repository of Greater Poland Oaths 1386-1444 (ROThA): Lessons in mark-up design. Prezentacja wygłoszona na konferencji: Diachronic corpora, genre and language change, University of Nottingham.

- Kopaczyk, J., M. Włodarczyk & E. Adamczyk. 2015. Electronic Repository of Greater Poland Oaths, 1386-1444 (ROThA): Lessons in text selection. Prezentacja wygłoszona na konferencji: d2e From data to evidence: Big data, rich data, uncharted data. University of Helsinki.

Oprogramowanie MANUS

System obsługi historycznych dokumentów źródłowych, dedykowany do budowania zaawansowanych baz i narzędzi dla projektów badawczych.

Internetowy system MANUS służy do opracowywania i udostępniania dokumentów źródłowych w standardzie TEI P5 XML (http://www.tei-c.org/). Jest to standard umożliwiający zawarcie bardzo bogatych metadanych dokumentów, ich struktury oraz reprezentacji tekstu w bogatych warstwach wielorakich znaczników (zobacz podręcznik). Standard ten zdobywa coraz większą popularność wśród naukowców humanistów różnych dziedzin do prezentowania tekstów do badań on–line. Ustrukturyzowana i ustandaryzowana forma plików XML sprawia, że są one łatwe do przetwarzania maszynowego co system MANUS wykorzystuje na wielu etapach.

System definiuje kilka schematów metadanych dokumentów TEI P5 dla różnego typu dokumentów: od skomplikowanych opisów rękopisów i starodruków (z bogatym nagłówkiem opisu fizycznego, stanu zachowania i zawartości), poprzez książki i rozdziały, czasopisma, numery i artykuły do pojedynczych dokumentów niepowiązanych żadną strukturą. System można tak skonfigurować, aby wyświetlał każdy z tych typów w oddzielnych (kilku) kolekcjach. Dla każdego z typów system udostępnia dedykowane, przyjazne użytkownikowi, formularze edycji jego metadanych TEI P5. Dzięki temu nie ma konieczności bezpośredniej edycji pliku XML, którego struktura jest bardzo złożona. Rozwiązanie takie nie tylko ułatwia wprowadzanie danych poprzez zastosowanie odpowiednich komponentów, ale także pozwala na sprawne korygowanie ewentualnych błędów. Dla zaawansowanych użytkowników istnieje możliwość podłączenia webowego edytora XML ze stowarzyszonej z systemem bazy danych eXistdb (http://www.exist-db.org/), lub wgrywanie do systemu plików XML edytowanych poza systemem. Redaktorzy mają także możliwość wgrywania do systemu skanów powiązanych z danym dokumentem TEI P5, a system automatycznie zrobi referencje na te skany w dokumencie.

System definiuje także schemat TEI P5 dla biogramów osób, które są autorami, redaktorami, tłumaczami, itp. dokumentów przechowywanych w bazie. Udostępnia strony grupujące dokumenty powiązane tymi relacjami z daną osobą, niezależnie od tego jakim pseudonimem/apelacją podpisały się w danym dokumencie.

System zintegrowany jest z silnikiem wyszukiwawczym Solr (http://lucene.apache.org/solr/), dając użytkownikowi zaawansowane możliwości wyszukiwania facetowego, w różnych warstwach tekstu i z uwzględnieniem lematyzacji języka polskiego (lub innego dostępnego w Solr). System można łatwo dostosować, by indeksował tylko wybrane węzły XML oraz wybrane warstwy tekstu, a także w ramach warstwy wybrane języki. Wyniki wyszukiwania można ograniczać do danej warstwy i języka oraz eksportować do plików tsv (text/tab-separated-values).

Przejrzysty interfejs graficzny portalu pozwala nie tylko na przeszukiwanie i przeglądanie zawartości plików XML, ale także na sprawne nawigowanie po powiązanych ze sobą danych, oraz na oglądanie stowarzyszonych skanów wraz z ich warstwami tekstu. Wszystko to dzięki rozbudowanemu podsystemowi zapytań XQuery, za pomocą którego MANUS łączy się ze stowarzyszoną bazą danych XML. Dodatkowe funkcje pracy z dokumentami implementowane są na potrzeby konkretnych projektów badawczych.